Recently I got to thinking about town criers in medieval Florence.

Now, I realize that this is not exactly the sort of thing that invades people's consciousnesses very often, but once in a while these things do crop up. This time, it stemmed from last week's blog post, in which I mentioned in passing that Dante's brother-in-law, Leone Poggi, was a town crier in Florence.

And then it dawned on me: when Dante was forced into exile as a result of (probably spurious and certainly politically motivated) criminal charges, somebody - some town crier, in fact - had to make the rounds and publicly announce the sentence. Had to bring the bad tidings to Dante's own home, not to mention the public piazzas and other busiest parts of the city.

Was it his brother-in-law who got stuck with this awkward task? If it was, wouldn't that likely make things really difficult the next time the whole family got together to celebrate a feast day? What would Dante's sister - Leone's wife - have thought? What about Dante's wife, Gemma? Sounds like a perfect recipe for family discord, doesn't it?

So I looked it up. And was relieved to find that it was not Leone who got assigned the job, but one of his five colleagues, a fellow named Duccio di Francesco. But of course, by the time I came across this reassuring tidbit of information, I was hooked, and found myself deeply engaged in trying to figure out the byzantine workings of this aspect of the Florentine justice system. Never mind the system as a whole - entire books have been written tracing Florentine law to its origins in Roman law and Germanic tribal law. I was concerned, at least for now, with the communication flow.

What I learned first was that it was all much more codified, and more complicated, than I would have guessed.

For one thing, there is some confusion in some of the histories about whether the

nuntio and the

bannitore (or

banditore) were the same, or whether they were different offices. The nuntio is a messenger who brought official notification to people in writing; the bannitore was a herald who made public announcements of the city's official proclamations, but who also bore responsibility in some cases for bringing this information directly to an individual. There is no reason why one man could not have performed both functions, yet it appears that (for most of the time, anyway) these were two separate offices.

The nuntio had to be a Florentine citizen, and had to have been resident in the city for at least ten years. He took an oath of office, posted a bond, and proudly wore a peaked wool cap decorated with four Florentine lilies, a symbol of office legally reserved for these civil employees. I do not know how many nuntii the city employed at any given time; it probably varied with the city budget.

The nuntio, when a person was accused of a crime, had the job of finding the accused and handing him a document which included the name of the judge of the case, the crime with which the recipient was accused, an invitation to present himself to the court within a specified time period, and the name of the messenger. This would typically be the first legal contact with the accused.

The bannitore, on the other hand, was one of a select group of six, one for each

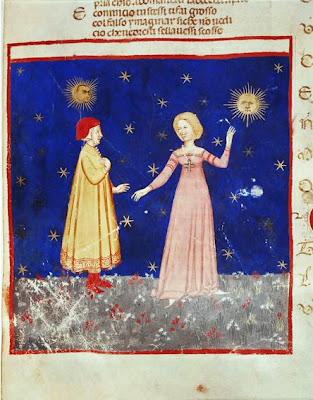

sesto of the city. Elected annually by the signory of Florence, these elite employees were required to be Florentine citizens, and they were required to identify their families. A bannitore had to be able to read and write, he needed to possess a "light and clear voice" and he had to own a small silver trumpet and be able to play short fanfares on it, to call people to hear his announcements. He needed to provide a good horse, one not also registered in the cavalry (no double duty here), and worth at least 20 florins of gold. (This was necessary because he would also be riding out to the suburbs and the surrounding countryside to perform his duties.)

If he met these exacting requirements and was chosen for the job (which, by the way, in 1307 paid exactly as much as a city trumpeter received, 3 lire per month), he would receive a new outfit of clothing twice a year, in a single color (either green or scarlet), and would be given a silver ornament called a

maspillos to wear around his neck.

(I've often thought that medieval livery had something in common with bridesmaids' dresses - just fine for its intended purpose, but not much use for anything else. Maybe that was the idea.)

His duties included announcing fairs and festivals, meetings of councils, levies of taxes, militia parades, bankruptcies, public auctions, and criminal and civil sentences. Prior to each announcement, he had to sound his trumpet call three times to call the people together. He was required to make his announcements at the gates of the city officer's palace, at the church of Or San Michele, and at a minimum of two public locations in each of the city's districts. Certain announcements concerning individuals (legal sentences, bankruptcies of individuals) had also to be announced near the individual's home.

Let's take a moment to talk about Florence's most famous bannitore, Antonio Pucci. Antonio, however admirable he may have been as a bannitore, was actually famous for his poetry, but his public career is nonetheless interesting. The son of a bronze caster who specialized in church bells, Antonio became a bellringer for the city, beginning in 1334, when he was probably about 25.

Perhaps he rang the city's bells to celebrate the victory of the Florentine militia over Padova in 1337, or the overthrow of the Duke of Athens in 1343. When the Black Death struck Florence with brute force in 1348, could it have resulted in the bannitore post opening up for Antonio? We don't know, but we do know that he continued overlapping both jobs for a while, and served as a bannitore for nearly twenty years.

In both of his public positions he would have been privy to the decisions of Florence's governing elite and would have played a role in communicating those decisions to the populace. Perhaps his job put him in a good position to observe the foibles of his fellow Florentines, because his poetry reflected some wry observations, like the one about the poultry vendor who sold him a dry old hen, or the ode to a notoriously sloppy barber.

But getting back to communications and to Dante's legal woes, I found an interesting breakdown of exactly how the legal process worked in Dante's case, in a book called

Contrary Commonwealth: The Theme of Exile in Medieval and Renaissance Italy, by Randolph Starn.

Dante, a member of the White Guelf party who had recently served as a member of Florence's ruling body, was in Rome as part of an official Florentine delegation to the Pope when the exiled Black Guelfs triumphantly re-entered Florence and turned the political tables, targeting prominent White Guelfs for retribution. I'll summarize the steps of their legal assault on the absent Dante here:

Step One: Messer Cante Gabrieli of Gubbio, the podestà (the foreign rector, or chief magistrate, chosen to serve for a half-year term, and in this case very much allied with Dante's political foes), appointed messer Paolo of Gubbio as special judge of crimes committed by public officials.

Step 2: Messer Paolo initiated proceedings and investigations against several of those who had recently served in the White Guelf government, and brought charges against Dante and three co-defendants: messer Palmiro Altoviti, Lippo Becchi, and Orlanduccio Orlandi. The four were accused of crimes-in-office including extortion, corruption, misappropriation of funds, fraud, accepting bribes, and plotting rebellion.

Is there any surviving evidence of any truth to these charges? No. They appear to have been wholly politically motivated. We cannot know for sure whether any specifics were cited, but if they were, they did not survive in the record.

Step 3: The court cited Dante and the other three and sent a nuntio (messenger) with written instructions, ordering them to appear by a certain deadline. Dante, you will recall, was in Rome at the time, probably with no direct knowledge that these things were going on. Thus, the nuntio would not have been able to hand him the document, and instead would have affixed it to the front door of Dante's home. All attempts to deliver the document would have been scrupulously recorded. At this point, Dante's legal status was that of

citatus - a person accused of a crime.

Step 4: When Dante and the others did not respond, they were subject to being "called under the ban" (

cridatio in bannum). It was at this point that the town crier, in this case Duccio di Francesco, rode forth on his horse worth at least 20 gold florins, blew three blasts on his silver trumpet, and voiced his message: "You must come."

He did this in a number of locations around the city, including just outside Dante's home. He must have done it at least twice in January 1302. He noted Dante's previous failure to appear (the fact that he was in Rome didn't count) and placed the poet under the ban of the commune of Florence; he was now required to pay a fine of 5000 florins within three days (though 15 days would have to pass before further action could be taken), and this was true even if he returned and proved his innocence, which would have been difficult under the circumstances, and would probably have exposed him to torture to elicit a confession.

Dante's status was now that of

bannitus.

After the total of 18 days had passed, thanks to Duccio's efforts, Dante's status was

exbannitus pro maleficio, meaning that he was considered a confessed criminal due to his contumacy (failure to appear). He had no right of appeal, and he had lost the rights of citizenship. Any citizen could assault or even assassinate him with impunity, provided the attack took place within Florentine territory.

And Dante may still not have known what was happening.

Step 5: On 27 January 1302 the magistrates pronounced a definitive sentence: since Dante and the others had not appeared to contest the accusations against them (probably a good idea on their parts, all things considered), they were considered confessed criminals and sentenced to pay the 5000 florins in fine within three days, plus any illicit gains to any legitimate claimants. If they did not - and how could they? - their property was to be confiscated and destroyed. Even if they did somehow manage to pay that vast sum of money within three days, they would still have been confined outside Tuscany for two years and banned forever from public office in Florence. It was now too late for innocence.

Step 6: The sentence was formalized and officially recorded by the court notary (ser Bonora da Pregio). Duccio di Francesco was among the witnesses.

On 10 March 1302, Dante and 14 other White Guelfs were sentenced to death by fire, should they ever return to Florentine territory. In 1311, an amnesty offered to those condemned in 1302 required an act of public penance, which Dante refused to perform. In 1315 he and his sons were proclaimed rebels and sentenced to be decapitated if they were captured. (One wonders if this superseded being burned at the stake.) On each of these occasions, the steps above (notification, public announcements, passage of a specified amount of time) were undertaken yet again.

The outcome? Dante never returned to his native Florence. He died in Ravenna in 1321, having written his masterwork

La Commedia while living in exile.

In 2008, the city council of Florence finally got around to voiding Dante's sentence.

*

Today, this blog has been in existence for exactly one year! Its readership has been growing, slowly at first, but faster all the time. We've covered a vast variety of topics, most of them at least loosely related to research - the process or the results. It's been fun, and I hope my readers have enjoyed it, too.

But although the blog is a year old, the little follower thingie on the right side of the page is only a couple of weeks old. If you'd like to help me celebrate this important milestone, perhaps you'd consider doing so by choosing to follow the blog.

Or, to be just a tad irreverent about it:

|

| Follow this blog, or the peacock gets it! |

Images in this post are in the public domain by virtue of having expired copyrights.

.jpg)

_-_The_Money_Changers_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

_Br%C3%BCder_(Pol_Limburg_006.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)