Luck, be a lady.

It would be hard to overstate the importance of Boethius's great work, The Consolation of Philosophy, among scholars in the middle ages and Renaissance. This profoundly influential book was written in the year 523 while the author was in prison awaiting trial (and execution the following year) on charges of treason against the Roman king Theodoric the Great.

Ancius Manlius Severinus Boethius, senator and consul, senior administrator to the king, translator, scholar, and philosopher, took the idea of Fortune and her wheel from earlier sources, but it was through his book that the motif became omnipresent throughout the middle ages. His influence can be traced through Dante, Boccaccio, Machiavelli, and even Shakespeare. The lady and her spinning disk (or sometimes orb) have a rich history in the visual arts, as well as in literature, theatre, and music.

Over the centuries she has remained controversial, as scholars debate whether she flies in the face of Free Will, or whether she is an agent of God's often inscrutable plan for mankind. Either way, those who ride the wheel up to the heights of worldly wealth and success are just as apt to ride it back down to ruin and devastation. The Wheel is never at rest.

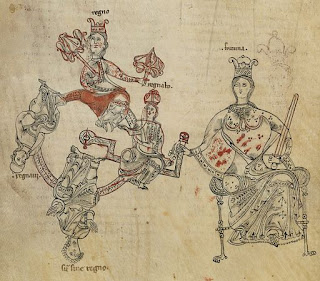

The Wheel is often depicted as showing an aspiring monarch on the left, climbing toward the top; a crowned monarch at the top; a third toppling down on the right, with the crown falling off; and the fourth on the ground, crownless, or even crushed beneath the Wheel. Illustrations often label these quarters regnabo, regno, regnavi, and sum sine regno, respectively (I shall reign, I reign, I have reigned, and I am without a kingdom). This fairly early version reverses the regnabo and regnavi positions:

Consolation of Philosophy

The premise of Boethius's book is that he, the disconsolate prisoner, who is in the process of losing every comfort, honor, possession, and vestige of safety he has ever had, is moping in his prison cell when he finds himself suddenly visited by an allegorical Lady - none other than the formidable Lady Philosophy herself.

Lady Philosophy urges Boethius to reject the wiles of Fortune. She takes it upon herself “to press home to the prisoner his need to reject power, wealth, and status in favor of the true good of wisdom,” as Seth Lerer observes in his introduction to David R. Slavitt’s translation. (She also shoos the Muses away, on the grounds that they are distracting the prisoner from the task at hand.)

"Fortune, of course, is a monster,” Philosophy observes, and Boethius is hardly in a position to disagree. “She toys with those for whom she intends catastrophe, showing her friendly face and lifting them up before dashing them down when they are least prepared for it.… you think that Fortune’s attitude toward you has changed. But you’re wrong. She hasn’t changed a bit. She was always whimsical, and she remains constant to her inconstancy. You were wrong to take her smiles seriously and to rely on them as the basis for your happiness. Now, what you have learned is that the changing face of blind power is unreliable – and always was.”

|

| Boethius and Philosophia |

Shifting to verse later in the chapter, she continues thus:

With an indifferent hand she spins the wheel,(All Boethius quotes translated by David R. Slavitt.)

and one or another

number comes up lucky, while the only constant

is change…

It’s a game she plays and a demonstration of

ruthless power,

a way to keep her devotees in a total subjection.

Classical origins

However influential Boethius may have been to later centuries, Fortuna and her wheel predated him. Worship of the Roman goddess Fortuna dates back to the earliest days of Rome, and she may have been derived from an even earlier goddess of the tribes of Latium, the area where Rome was founded.

Her name may be rooted in the Latin word meaning "to bring, to receive, to give." Alternatively, it may come from the Etruscan goddess Voltumna (possibly related to the Roman goddess Volumna). Voltumna had to do with the turn of the seasons, not unlike the spinning of Fortuna's wheel. Volumna protected children, while Fortuna predicted the fate of children at their birth, particularly firstborn children, in her aspect of Fortuna Primigenia. She has also been linked with the Egyptian goddess Isis via an amulet found in Pompeii, with the Greek goddess Tyche, and with another Etruscan deity, Nortia.

This little household deity depicts Fortuna with some of the same iconographic devices as both Tyche and Isis:

Fortuna had temples in Rome at a very early date. Her cult may have begun with Ancus Marius, the fourth king of Rome (642-617 BCE), or possibly with Servius Tullius, the sixth king of Rome (575-535 BCE) and the second of the Etruscan kings. Servius Tullius erected the first Roman temple to Fortuna, where her cult was celebrated on Midsummer's Day and her festival on June 11, but her greatest temple was the oracle and sanctuary at Praeneste (now Palestrina), not far from Rome. The oracle there involved a young boy who picked out a fortune from among many written on oak rods.

A little digression about that Etruscan king of Rome, Servius Tullius: He ruled Rome for over 40 years, riding high on Fortune's wheel, but the day came when the wheel moved again, to his detriment and at lightning speed. This picture shows his daughter Tullia (not exactly Daddy's little girl) running over her father with her chariot, in a successful bid to seize the kingship for her husband. Servius Tullius thus moved through regnabo to regno and stayed there a long time, and then quite precipitously tumbled through regnavi to arrive at sum sine regno (or perhaps even one step further, to whatever the Latin word is for "smooshed"). Tullia, meanwhile, was concentrating hard on regnabo.

Classical writers added to Fortuna's fame. In 55 BCE, Seneca has the chorus of his tragedy Agamemnon address the goddess, in a remarkable speech that has a lot in common with "Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown." It includes this:

Whatever Fortune has raised on high, she lifts but to bring low. Modest estate has longer life; then happy he whoe'er, content with the common lot, with safe breeze hugs the shore, and, fearing to trust his skiff to the wider sea, with unambitious oar keeps close to land.

|

| Seneca |

Early churchmen couldn't ignore her, either. We find St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430) casting her as essentially an employee of God. Since God knows the cause of every event, though man does not, all things are part of his plan, and Fortuna is therefore working in harmony with God's will. We will see more along these lines in Part 2 of this post, when we get to Dante.

|

| St. Augustine |

The Iconography of Fortune

We've seen a few portrayals of Fortuna, but there are many more, displaying quite a variety of features. Some of the earliest depictions show the goddess atop the wheel, turning it with her feet; others show her treading on an orb, like a trained circus animal, trying to keep her balance. Here's a late treatment of this idea:

After around 1100, though, Fortuna acquires some stability, and it is only the hapless humans mounted on her wheel who suffer from a lack of equilibrium.

Fortuna's wheel was sometimes turned by a crank, sometimes by her hand. In some cases it is not obvious how the wheel is being turned. In an interesting article, "Mechanical Wheels of Fortune 1100-1547," Alan H. Nelson observes that early illustrations suggest the model for the wheel was not a simple cartwheel, but rather a mill wheel, or perhaps a spinning wheel. He also says that early depictions tend to show mechanical details, but later pictures are more abstract.

Fortuna herself may be shown as two-faced, with one side light and the other dark (or one side frowning and the other smiling), or as blinded or blindfolded. This latter characteristic she shares with illustrations of Justice, but unlike Justice, Fortuna never holds a scale: fairness, in the human sense, is not what drives her.

She is associated instead with such motifs as the cornucopia, the rudder, and, of course, the wheel itself.

Sometimes the humans on Fortuna's wheel are shown as specific individuals: Croesus, or Boethius himself, or, as in this illustration, Tancred the king of Sicily at the bottom of the wheel and his nemesis Henry VI, king of the Romans, at the top:

I won't go into Tancred's story here, though his unfortunate habit of capturing the wives of his opponents does tempt me. I'll just note that he was a small man, which apparently earned him the nickname "Tancredulus" thanks to the poet Pietro of Eboli. (I can think of one other possibility for that name. Richard I of England is said to have given Tancred a sword he claimed was Excalibur itself, as a gesture of friendship. That would seem to involve a certain level of credulity.)

The fall of Troy is another historical event often associated with the Wheel:

Usually those who ride the wheel are men, but once in a while you find a woman, as here:

There's more to say about Fortuna and her wheel, but it will have to wait until my next post. Come back in a week or two (I hope...) to read about Fortuna as she appears in Dante, Boccaccio, and Machiavelli; in the English playwrights; in theatrical performances and processions; and in medieval song, such as Carmina Burana.

2 comments:

Hi! I'd love to know the source of all your illustrations!

I often use Wikimedia Commons - Images, which has a lot of public domain images available.

Post a Comment