|

| Judith Starkston |

Who were the Trojans?

This turns out to be a very tricky question.

|

| The walls of Troy |

Part I: The Greek Assumption

Until the 19th century when German businessman Heinrich Schliemann followed his idiosyncratic dream and found Troy on the coast of Turkey near the Hellespont, many people thought “Troy” was the stuff of myth. We can now say with reasonable certainty that we know where Troy existed. A contemporary dig, begun under the leadership of the German archaeologist Manfred Korfmann, has confirmed the earlier identification and revealed a great deal more about the nature of this famous city.

|

| Heinrich Schliemann |

However, knowing the city’s location doesn’t tell us what cultural/ethnic group the residents belonged to, what language they spoke, what their religious system was.

If you read the Iliad, you would think you had the answer—the Trojans were basically Greeks. Rather like Star Trek, heroes from the opposing sides in Homer’s poem can carry on conversations without any translators. In the Iliad the Trojans have temples to Apollo and Athena, who were also Greek gods. Based on Homer, scholars from past generations sometimes concluded that the residents of Troy were culturally the same as the Greeks who sailed across the Aegean to attack their city. When I started writing my novel about Briseis, a woman taken captive by the Greeks, I assumed the same thing.

|

| Temple of Apollo Smintheon near Troy |

It’s true that Greeks in the Archaic period, well after the “Homeric” period of Troy, colonized the western coast of Anatolia (modern Turkey). It’s also true that the Greeks had powerful outposts there in the relevant period—the Late Bronze Age, such as at Miletus (Milawata in Hittite correspondence). Mycenaean Greek pottery and other signs of trade influence have been found at Troy. The Trojans interacted with the Greeks in ways both friendly and warlike.

Nonetheless, the assumption that the Trojans were a variety of Greek is wrong.

Part II: The Hittite Connection; The Trojans are Luwians

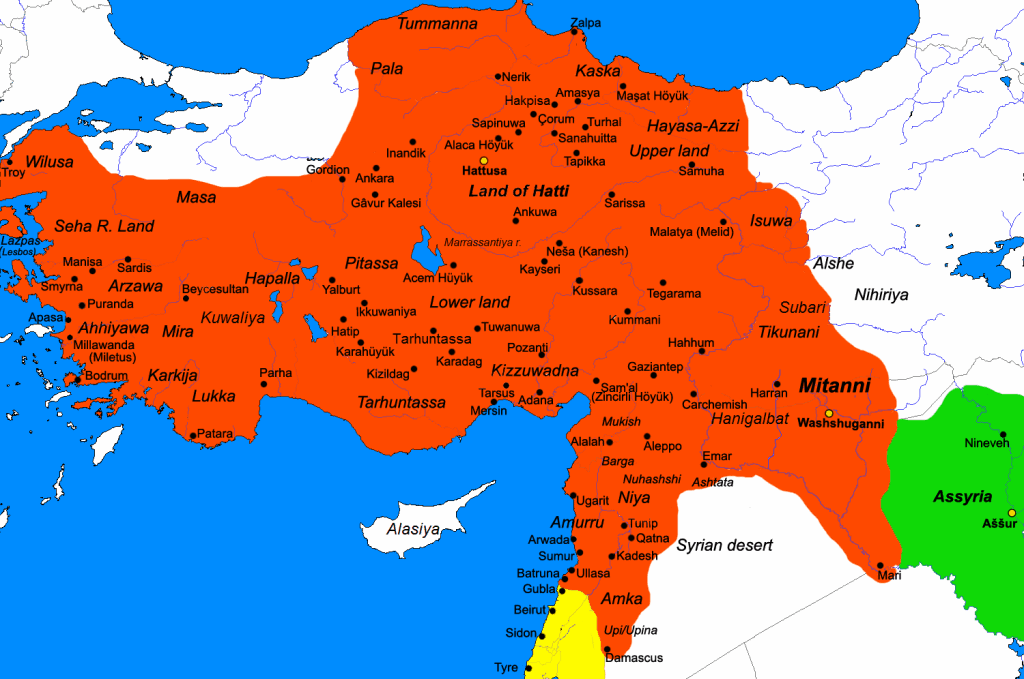

Scholarly opinion now leans toward identifying the Trojans as part of the Luwian peoples who occupied large swaths of what we now call Turkey, primarily in the Western and Southeastern portions, throughout the Bronze Ages.

|

| Map of the Hittite Empire, Luwian region shown on western part of map |

So who were the Luwians and how does that connect the Trojans to the Hittites?

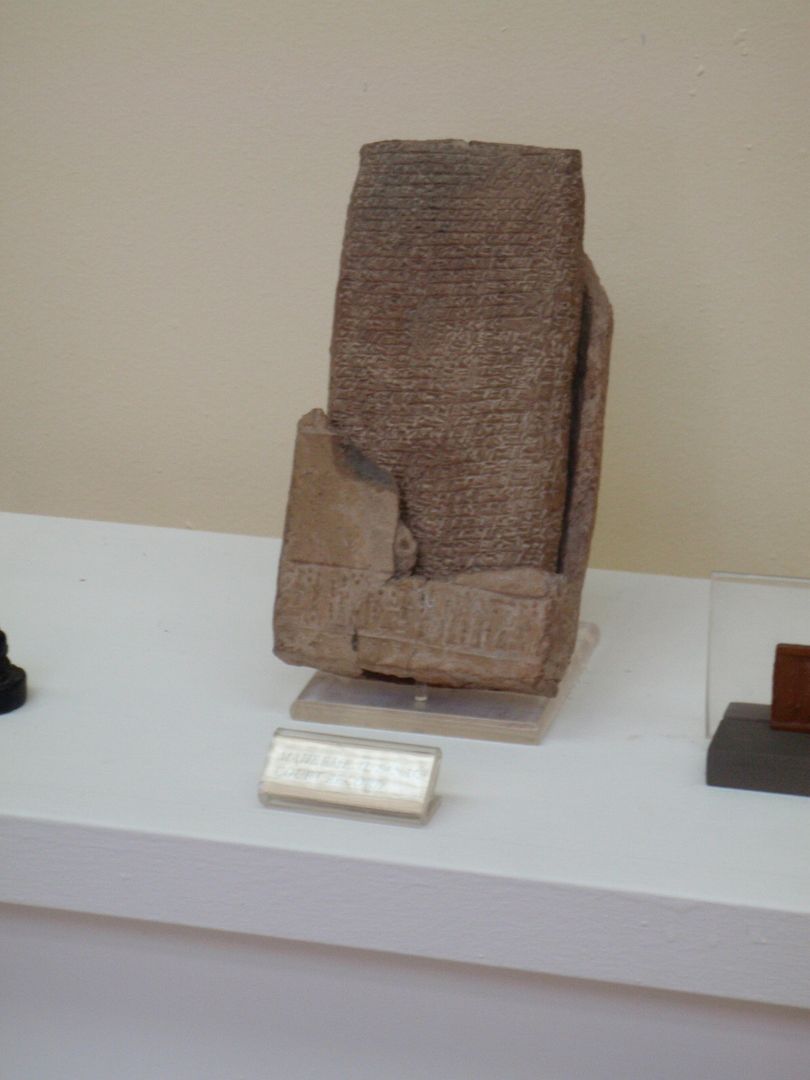

A key issue is that we know a lot about the Hittites from their written records, but no such libraries of clay tablets have been found in the western Luwian areas such as Troy. Most of what we know about the Luwians is found in the Hittite texts which include a lot of Luwian information in the Luwian language. It’s a lopsided filter through which to view a people, but it’s the best we can do at this point until tablets are found at a Luwian site. Hence the Hittite connection: If you want to understand the Trojans/Luwians, by necessity you must examine the Hittites. That is why so much of the information on this website is about Hittites.

|

| Cuneiform tablet |

Beyond the lack of extant tablets from Luwian sites, studying the Hittites to understand the Luwians/Trojans is useful because they are closely related culturally and religiously. If we could go back in time and watch the two cultures, we would no doubt realize that the two peoples did a number of things differently, but the similarities would probably outnumber the differences overall. So in the absence of a large body of information about the Luwians/Trojans, an historian or historical fiction writer can turn to the Hittites and extrapolate with a fair sense of being roughly on track.

|

| Hittite bronze statue of a mother and child, possibly a goddess |

Part III: A summary of who the Luwians were and the ways the Luwians and Hittites influenced each other

The Luwians and Hittites were Indo-European. Scholars are still debating at what time period these Indo-European groups arrived in the area of Anatolia and from what region they might have come, but they differ from their eastern neighbors such as the Assyrians, Babylonians, etc. who have Semitic or other origins. Luwian, as a language, is part of a closely related group including Hittite, Palaic, Lycian, Lydian, and Carian. All of these languages of ancient Anatolia are derived from a prehistoric language we may call “Proto-Anatolian” which in turn derived from “Proto-Indo-European.” Indo-European encompasses most of the languages of Europe—so to that extent the Luwians’ language and the Luwians themselves are remote “cousins” of Greek, but they had separate developments from very early on. (For more on Indo-European)

Linguistically the Hittites and Luwians were close in many ways, and language is a significant cultural determinor. The Hittite language directly borrowed many Luwian words. Indeed by the height of the Hittite empire, a majority of the residents of Hattusa, the Hittite capital, spoke Luwian. The Hittite king and royal family spoke both Luwian and Hittite.

|

| Hieroglyphic seal, photo by Baris Askin, The Troy Guide |

We cannot be absolutely certain that Luwian, rather than Palaic or some other similar language, was spoken in the region around Troy, but it seems the most likely choice based on the evidence. The only piece of writing from Troy, a hieroglyphic seal, is written in Luwian. (Luwian was written in both cuneiform and hieroglyphics depending on the context.) Also the oldest form of the name for Troy known to the Hittites, Wilusiya-, is a Luwian formulation. The later Hittite name for Troy is Wilusa.

The Luwians as a people never formed one unified state. By the Late Bronze Age the western Luwian lands were roughly grouped into five states, Troy/Wilusa being one of them. They occasionally acted together in war. Treaties exist between these states and the huge Hittite empire to the east of these lands. The Hittites are dominant in these treaties and other correspondence between them. Although these Luwian areas are frequently not formally part of the Hittite empire, they are under its political influence.

|

| Hittite king offering to a god, photo by Dick Osseman |

A wide variety of religious influences between the Hittites and Luwians can be found in the written evidence. Luwian cultic texts were incorporated from an early period into the Hittite religious texts. That means the actual ritual practices of the Hittites would include Luwian elements.

In the Hittite law codes, there are mentions of separate penalties for Luwians as opposed to Hittites. This means that the two peoples interacted closely and constantly, but it also means that the Hittites viewed the Luwians as a people separate from themselves.

Interesting historical footnote:

Why did Hittite texts survive and not Luwian?

Only one piece of writing has been found at Troy, a hieroglyphic seal, so a logical assumption would seem at first to be that the Trojans didn’t write or read. However, the Hittite side of correspondence and treaties with the Trojans and others in this Luwian area are extant, so we know that the kings of Troy/Wilusa had scribes and written records.

So why haven’t tablets at Troy been found? You’d think clay tablets would survive—after all pottery shards pop up everywhere in archaeological sites.

Pots are fired, clay tablets are not. Clay tablets melt away into the dust unless a catastrophic fire burns so hot and long that the tablets are in essence fired. The absence of a “library” at Troy may perhaps be explained by something as simple and arbitrary as the lack of a hot-enough destructive fire in the correct buildings.

What about Greeks and writing?

The Mycenaean Greeks were also literate—they wrote a form of Greek called Linear B and also corresponded with the Hittites.

|

| Linear B tablet and drawing |

Unlike the Hittites, they did not use writing to record myths, laws, and other interesting cultural documents. They used writing primarily as financial record keeping.

Writing was lost to the Greek world after the Late Bronze Age and was rediscovered with a new alphabetic writing system around the 8th century BC. From that time on they used more or less the letters we are familiar with as Greek. Around the time of this rebirth of literacy, the oral poems we know as the Iliad and Odyssey were put into written form.

***

Many thanks to Judith, who I hope will be back with more guest posts talking about her research into these long-ago civilizations.

1 comment:

Absolutely fascinating! Thank you for this.

Post a Comment