O Fortune,

like the moon

you are changeable,

ever waxing

and waning;

hateful life

first oppresses

and then soothes

as fancy takes it;

poverty

and power

it melts them like ice.

Fate - monstrous

and empty,

you whirling wheel,

you are malevolent,

well-being is vain

and always fades to nothing,

shadowed

and veiled

you plague me too;

now through the game

I bring my bare back

to your villainy.

(I would love to credit the translator of the text above, but although this version appears about forty gazillion times all over the place, nobody seems to bother to list the translator's name. So let us figuratively lay a wreath on the Tomb of the Unknown Translator - whether it be occupied yet or not - and acknowledge our debt to the skilled and too-easily-forgotten people who render things comprehensible for the rest of us. I, for one, need them. My knowledge of Latin is nil. And don't even get me started on all the scholarly articles that show off by including quotes in several languages and not translating them, because naturally if we're smart enough to read their work, we're supposed to know all those languages, right? Harrumph. End of rant. We now return you to your regularly scheduled blog post.)

In the previous post we examined the role of Fortune and her wheel in Boethius's great work, The Consolation of Philosophy. We took a look at the classical origins of the goddess Fortuna, and briefly discussed the iconography. If you'd like to read that post before continuing, you'll find it here:

http://historicalfictionresearch.blogspot.com/2017/01/the-wheel-of-fortune-part-1-of-2.html

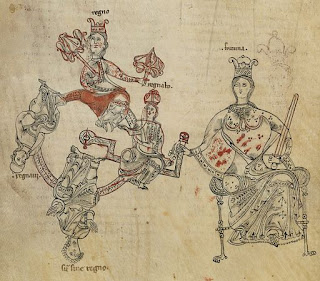

The illustration above, as well as the one at the top of this post, is from the medieval manuscript containing the famous Carmina Burana song collection (ca. 1235). Benjamin Bagby, leader of the medieval music group Sequentia, has described this collection as evidencing "an almost obsessive fascination with Fortuna." Consisting of bawdy and satirical songs from the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries, mostly in medieval Latin but with some of the poems in other European languages, Carmina Burana may well have originated with the irrepressible Goliards, young clerics, often second sons cut off from inheritance and therefore given over to the church despite a lack of vocation. Many of the poems, most of which are anonymous, satirize the Church.

Most of us know Carmina Burana best from Carl Orff's cantata based on the songs, written in the 1930s. Here you will find a link to a popular performance of Orff's dramatic version of the song quoted above: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GXFSK0ogeg4

And if you like to season the sublime with a touch of the ridiculous, here's one of the "misheard lyrics" versions: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nIwrgAnx6Q8

Recently I attended a Sequentia concert in which another Fortune-related song from Carmina Burana was featured. The translations of the lyrics (by Bagby, in this case) were projected onto the wall behind the performers, for the benefit of the audience. At one point, this occasioned a ripple of laughter through the audience, which swelled into general hilarity despite the song's overall serious tone. I'll quote those lines here and leave it to you to figure out what caused so much amusement:

O Fortune, changing and unstable, your tribunal and judges are also unstable. You prepare huge gifts for him who you would tickle with favors as he arrives at the top of your wheel.

But your gifts are unsure, and finally everything is reversed; you raise up the poor man from his filth and you make the loudmouth into a statesman.

Fortuna in Dante

It's in the seventh canto of the Inferno that Dante's guide, Virgil, explains to him the nature of Fortune. Dante asks Virgil, "This Fortune that you touch on here, what is it, that has the goods of the world in its clutches?"

Virgil replies:

He whose wisdom transcends all things fashioned the heavens, and he gave them governors who see that every part shines to every other part,(translation by Robert M. Durling)

distributing the light equally. Similarly, for worldly splendors he ordained a general minister and leader

who would transfer from time to time the empty goods from one people to another, from one family to another, beyond any human wisdom's power to prevent;

therefore one people rules and another languishes, according to her judgment, that is hidden, like the snake in grass.

Your knowledge cannot resist her; she foresees, judges, and carries out her rule as the other gods do theirs.

Her permutations know no truce; necessity makes her swift, so thick come those who must have their turns.

This is she who is so crucified even by those who should give her praise, wrongly blaming and speaking ill of her;

but she is blessed in herself and does not listen: with the other first creatures, she gladly turns her sphere and rejoices in her blessedness.

Dante the author (as opposed to Dante the character) has made Fortune a Divine Intelligence, a "general minister and leader" - or, as Dante scholar Christopher Kleinhenz says, "an angel, above rebuke."

|

| Canto &7 |

This exchange occurs as Dante and Virgin approach the fourth circle, where the avaricious and the prodigal are punished. These damned souls must roll huge stones in opposing directions, moving in a semicircle. When they meet head-on, they clash, then turn and retrace their steps. Thus, they never complete a circuit. Unlike Fortune's wheel, they can never go full circle.

|

| Boccaccio |

Fortuna in Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccacio draws on Boethius for his concept of Fortune's double nature in his lesser known works. Of his masterpiece, the Decameron, Teodolinda Barolini writes, "The Decameron could be pictured as a wheel - Fortune's wheel, the wheel of life - on which the brigata turns, coming back transformed to the point of departure."

The tales told on Day 2 of the Decameron especially seem to depend on the unpredictability of Fortune (cf. Andreuccio).

Vincenzo Cioffari observes, "In Boccaccio this disinterested tranquility of Fortune is substituted by a mischievous and interested cunning... In the Decameron the primary function of Fortune is to determine the outcome of a course of action..."

Boccaccio, says Cioffari, does not limit himself to discussing wealth and power as Fortune's sole currency, but adds to them the idea of sensual pleasures.

Still, Boccaccio sees Fortune as an instrument of Divine Will. As Cioffari says, "Far from being blind it has a hundred eyes because, although its activity may not be apparent to Man, it is carrying out the Divine Will just as much as Nature."

Boccaccio's Fortune is a capricious woman, ever-changing, whimsical.

Fortuna in Machiavelli

Unsurprisingly, Niccoló Machiavelli's concept of Fortune is less noble than Dante's and less playful than Boccaccio's. You could almost describe it is cynical, or perhaps - Machiavellian.

Here is the famous passage from The Prince concerning Fortune:

It is not unknown to me how many men have had, and still have, the opinion that the affairs of the world are in such wise governed by fortune and by God that men with their wisdom cannot direct them and that no one can even help them... Sometimes pondering over this, I am in some degree inclined to their opinion. Nevertheless, not to extinguish our free will, I hold it to be true that Fortune is the arbiter of one-half of our actions, but that she still leaves us to direct the other half, or perhaps a little less.(Translation by W. K. Marriott)

"Half, or a little less." Machiavelli's Fortune is a force of nature, but human beings are not entirely helpless against her:

I compare her to one of those raging rivers, which when in flood overflows the plains, sweeping away trees and buildings, bearing away the soil from place to place; everything flies before it, all yield to its violence, without being able in any way to withstand it; and yet, though its nature be such, it does not follow therefore that men, when the weather becomes fair, shall not make provision, both with defences and barriers, in such a manner that, rising again, the waters may pass away by canal, and their force be neither so unrestrained nor so dangerous. (Trans. WKM)And being Machiavelli, he couldn't let the matter drop without a brief foray into misogyny:

For my part I consider that it is better to be adventurous than cautious, because Fortune is a woman, and if you wish to keep her under it is necessary to beat and ill-use her; and it is seen that she allows herself to be mastered by the adventurous rather than by those who go to work more coldly. She is, therefore, always, woman-like, a lover of young men, because they are less cautious, more violent, and with more audacity command her. (Trans. WKM)Machiavelli's Fortune has a total disregard for human feelings. Her actions appear cruel, but in truth are the result of indifference. She does not favor personal glory and is apt to target the successful, arranging for an ignominious fall just as her victim approaches his goal. She prefers discord among men. Cesare Borgia, for example, was born under a Fortune of "extraordinary and extreme malignity."

| |

| Cesare Borgia |

Fortune's Wheel in Theater

Here we venture into the area of mechanical wheels. Unfortunately, I've not been able to find illustrations that are both useful and available, so we will have to content ourselves with a couple of descriptions.

The earliest example is a wheel at the Benedictine abbey of Fécamp in Normandy, around the year 1100. We have a delightful description by a visitor to the abbey, Bishop Balderic of Dol:

Then, in the same church, I saw a wheel, which by some means unknown to me descended and ascended, rotating continually. At first I took this wheel to be an empty thing, until reason recalled me from this interpretation. I knew from this evidence of the ancient Fathers that the wheel of Fortune - which is an enemy of all mankind throughout the ages - hurls us many times into the depths; again, false deceiver that she is, she promises to raise us to the extreme heights, but then she turns in a circle, that we should beware the wild whirling of fortune, nor trust the instability of that happy-seeming and evilly seductive wheel: concerning these things those wise, ancient doctors have not left us uninstructed. By revealing these things, they have brought us to understanding.(This translation appears in an article by Alan H. Nelson and is, presumably by him.)

An enactment of the Wheel, complete with four realistic figures of rising and falling kings, appears in a drama by Adam de la Halle (Jeu de la feuillé, first produced in Arras in 1276).

Live actors, however, stole the show in a morality play by Antoine Vérard published in 1498 (though performed as early as 1439). In this play, called Bien-Advisé Mal-Advisé, the figures at the Regnabo and Regno positions experience the torments of Hell, while Regnavi and Sine Regno achieve salvation.

Other examples vary: devils taking the place of kings, children as actors, and an elaborate wheel with a metal mirror at the center, constructed by the versatile Giovanni Cellini, engineer, professional musician, and father of famed goldsmith and diarist Benvenuto Cellini. (Click here for an earlier blog post about this father-son pair.)

In 1515, the city of Bruges held a pageant in honor of Charles V, Count of Flanders and future emperor. Judging by his portraits, Charles had a somewhat unusual chin:

|

| Guess which one? |

Be that as it may, the pageant featured a Wheel of Fortune with two Virtues in attendance, who were able to assist the young monarch in bringing the Wheel to a standstill. A second Wheel in another part of the pageant featured Extravagance, the god Mars, the City of Bruges (played by a woman), and Negotiation.

|

| A later pageant at Bruges |

The Wheel of Fortune in Shakespeare

It has been said that Shakespeare's history plays draw heavily on the idea of the Wheel, particularly the Richard II - Henry IV - Henry V sequence, with Richard on top in the Regno position at first, and Bolingbroke occupying the Regnabo spot.

Raymond Chapman, a Shakespearean scholar, notes all the "up and down" imagery in those plays, which he calls "a relentless alternation of rise and fall." Or, as Richard himself says, "Conveyors are you all, that rise thus nimbly by a true king's fall."

Minor digression: Shakespeare is not the only English playwright to use this concept. His predecessor William Collingbourne (1435-1484), in his Mirror for Magistrates, says this:

We knowe, say they, the course of Fortunes whele,

How constantly it whyrleth styll about,

Arrearing nowe, whyle elder headlong reele,

Howe all the riders alway hange in doubt.

But what for that? We count him but a lowte

That stickes to mount, and basely like a beast

Lyves temperately for feare of blockam feast.

Collingbourne was no friend to King Richard III, and is in fact known for posting a scurrilous couplet on the door of St. Paul's Cathedral in July of 1484. It read as follows:

The Catte, the Ratte and Lovell our dogge(That would be William Catesby, who had a white cat on his device; Richard Ratcliffe; and Francis Viscount Lovell, who had a silver wolf as his emblem. The hogge, of course, is Richard himself, whose badge bore the white boar. Not coincidentally, Collingbourne was executed for treason that same year.)

rulyth all Englande under a hogge.

More modern Wheels of Fortune

Probably the context in which we see the Wheel most often these days is in the Major Arcana of the Tarot deck. Here are some fairly venerable examples:

And finally, let me leave you with the thing most people today think about when we refer to the Wheel of Fortune: