In my last post I promised a look at Florence's medieval population figures, with at least a cursory glance at our sources for that information and the processes historians use to figure out how many people lived in a given place at a given time.

But before we go into generalities, I'd like to take a look at one specific -- and extraordinary -- source for Florence, circa 1338.

In 1338, the ravages of the Black Death are still ten years in the future, though other pestilences have recently wrought havoc on a smaller scale, as have natural disasters and food shortages. Dante has been dead for 17 years. Florence's extraordinary century of growth -- the 13th century -- is over, and Florence is now the dominant military and commercial power in Tuscany. She is a wealthy city, and much of her wealth comes from the wool industry. Her merchants and bankers are famous throughout the world.

And one proud Florentine, the chronicler Giovanni Villani, elected to give us a detailed portrait of his city, including numbers. Lots of numbers. There is, of course, no way to verify his every claim, but modern historians have generally been impressed with how closely his figures tally with those they've arrived at after much forensic work.

|

| Giovanni Villani |

Villani was in a good position to give us this snapshot of his city in the year 1338. Born into a prosperous merchant family, he was a banker and a public servant as well as a historian. He was an agent, a shareholder, and eventually a partner in the famous Peruzzi banking company; a member and sometime officer of the powerful Arte di Calimala (wool-finishers guild); and he served his city as one of its priors (the nine-member elected government) on several different occasions. In addition to that, he was deputized in 1324 to oversee the rebuilding of the city's walls, and after the famine of 1328 he served as a magistrate in charge of provisioning the city and distributing grain to the citizens of Florence. He also served in the Florentine army.

He knew Florence, knew her physical properties, her politics, her business ventures, her military activities, her people.

Here are a few of the things he has told us about Florence in 1338:

First, based on the consumption of grain, he calculated that Florence had about 90,000 mouths to feed. Modern scholars believe the total population to have been somewhere between 100,000 and 120,000 at that time; however, Villani explicitly says that he did not include members of religious orders or foreigners (foreigners being non-citizens, and there would have been a lot of them because of the influx of people from the countryside during the recent famine, people who wanted to take advantage of Florence's grain provisions). Allowing for those two categories, Villani's figures appear to be fairly accurate.

|

| Distribution of grain |

He tells us that about 25,000 men between the ages of 15 and 70 were capable of bearing arms, and in time of war they would be joined by another 80,000 men from the surrounding countryside (the contado).

Between 5,500 and 6,000 infant baptisms were performed in Florence's Baptistery that year.

|

| Three views, old and new, of the Baptistery |

Some 8,000 to 10,000 children, both boys and girls, were learning to read in elementary schools. Six hundred boys were enrolled in higher level schools to learn grammar and logic.

The city housed 110 churches, of which 57 were parish churches and the rest belonged to the various religious orders.

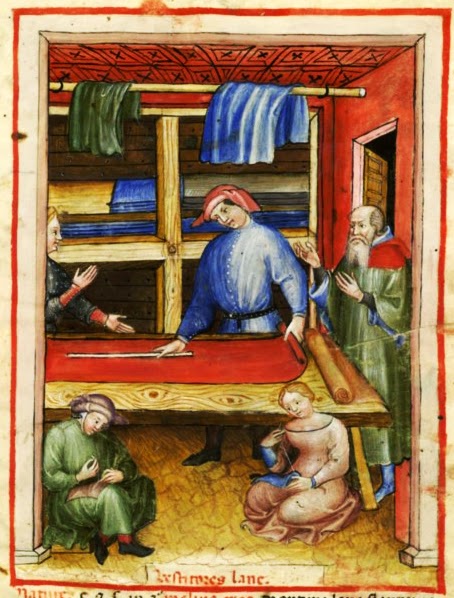

Over 200 workshops associated with the wool trade employed some 30,000 people, producing 70,000 to 80,000 bolts of cloth with a total value of more than one million two hundred thousand gold florins, a third of which was paid out as wages.

Florence had 80 banks, 600 notaries, 60 physicians and surgeons, and 100 apothecaries to serve its populace.

|

| Apothecary |

In a year the city went through enough grain and wine and meat animals to allow us to say that each individual in the city consumed, on average, 530 pounds of grain, 54 gallons of wine, and 88 pounds of meat, according to the calculations in Gene Brucker's book Florence: The Golden Age, 1138-1737. That meant a total of 4,000 cows and calves per year, as well as 60,000 geldings and sheep, 20,000 goats, and 30,000 pigs.

Brucker also has an interesting diagram that illustrates the population breakdown. Out of 500 people representing a cross-section of the entire population of Florence, he tells us, the distribution includes the following:

- 1 moneylender or judge

- 2 priests

- 1 monk

- 3 nuns

- 60 scholars: 3 studying grammar, 7 studying the abacus, and 50 learning to read

- 3 notaries

- 1 doctor or apothecary

- 1 baker

- 139 (potential) soldiers

- 8 noblemen

- 2 merchants traveling outside the city

- 8 foreigners (visitors or soldiers)

- 168 earning their living from the wool trade (one of whom actually owned a wool workshop)

Images in this post are in the public domain.